With the release of Graceland on 26 August 1986, the South Africa of the townships under a state of emergency, Zulu miners’ hostels and the rhythms of Mbaqanga and Shangaan, the musician Paul Simon flew in through the large window to land in the brand-new CD players of Western music lovers. Three years earlier, on the basis of a South African cassette, the Frenchwoman Lizzy Mercier Descloux had already made the trip to Egoli, the “City of Gold” as Johannesburg is nicknamed, to record her album Zulu Rock, crowned by the single “Mais où sont passées les gazelles ?”

According to her producer, Michel Esteban, Paul Simon had undoubtedly listened to this seminal record. But the American singer-songwriter had been singing in another category since his debut in a duo with Art Garfunkel in the late 1950s: the baby boomers. History tells us that it was also on listening to a South African cassette – the compilation Gumboots: Accordion Jive Hits, Volume 2 (released by the major South African label Gallo) – that the native of Newark, New Jersey was seized by a passion, during the summer of 1985, for these southern African grooves that were “vaguely like 50s rock’n’roll out of the Atlantic Records school of simple three-chord pop hits: ‘Mr Lee’ by the Bobettes”, and “familiar and foreign-sounding at the same time”, as he explains in the liner notes of the album he would produce himself.

Then aged 44, Paul Simon was at a low point following the critical and public failure of his album Hearts and Bones, released in 1983. His initial idea was to record an album of South African covers based on his “El Condor Pasa”, inspired by Peruvian folklore. The South African producer Hilton Rosenthal, behind the success of South Africa’s first interracial group Juluka (which included the singer Johnny Clegg), instead advised Paul Simon to come to Johannesburg to write his album. South Africa was experiencing the final years of the apartheid regime. As Paul Simon would later recognise, it was “too bad [the record] was not from Zaire (now the DRC) or Nigeria”.

Since the 1960s, civil rights organisations – firstly in the United Kingdom and then the United States – had been calling for a cultural boycott of South Africa. The United Nations adopted its own resolution in December 1980. From Peter Gabriel’s “Biko” (1980) to “Free Mandela” by Jerry Dammers’s Spatial AKA Orchestra (1984), the South African cause took over the airwaves of the West. In the United States, under the aegis of the guitarist Steve Van Zandt, the “Artists United Against Apartheid” lashed out in “Sun City” – from the name of a South African resort located in the Bophuthatswana homeland – at their colleagues handsomely paid to perform in the enclave.

Heeding the advice of Quincy Jones and Harry Belafonte, two leading figures in African-American civil rights, Simon went to South Africa, but did not agree to meet with officials from the ANC, then an underground organisation. “I knew I would be criticised if I went, even though I wasn’t going to perform for segregated audiences”, he would later explain to the New York Times. “I was following my musical instincts in wanting to work with people whose music I greatly admired”.

He was on the side of artists rather than politicians: during recording sessions in Johannesburg, Paul Simon ensured that his African colleagues were treated on the same footing as the Western musicians. The artist also agreed to share the credits. It was a sufficiently ethical agreement that the Union of Black South African Musicians, initially resistant to Paul Simon’s arrival, officially invited him to record in the country. When these sessions were transferred to New York and London, Paul ensured VIP treatment for his musicians. Ray Phiri, the singer and guitarist from the group Stimela, and Joseph Shabalala, the leader of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, who would go on to have an international career thanks to the recognition of Graceland, would continue to support Paul Simon. That was not the case for all South African musicians, however. The late trombonist Jonas Gwangwa, who then led the group Amandla, the ANC’s cultural ambassador, joked: “So, it has taken another white man to discover my people?”

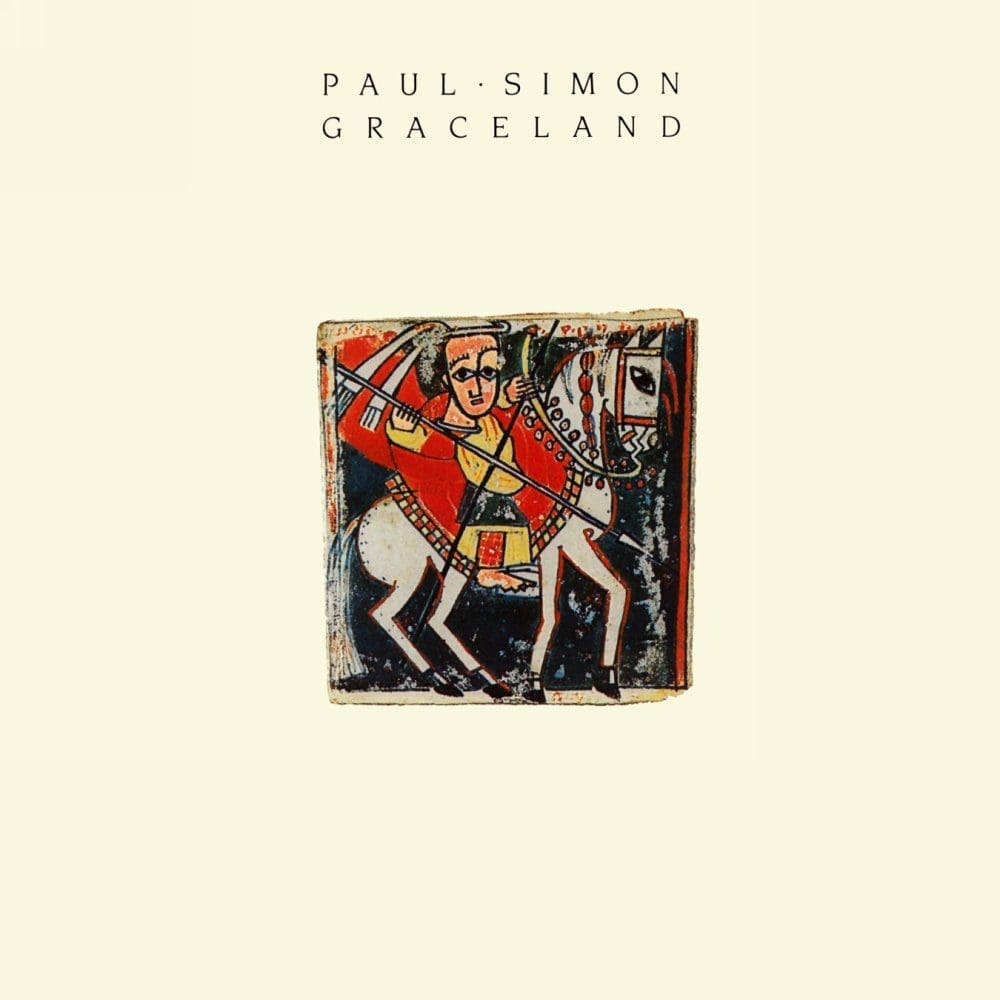

With 14 million copies sold since its release, Graceland became a benchmark record for what was then called World Music. In January 1992, Paul Simon would experience redemption by being the first Western artist to perform in post-apartheid South Africa, posing for immortality alongside a Nelson Mandela whom he had described only six years earlier as “a communist”, echoing the official discourse of the American government…