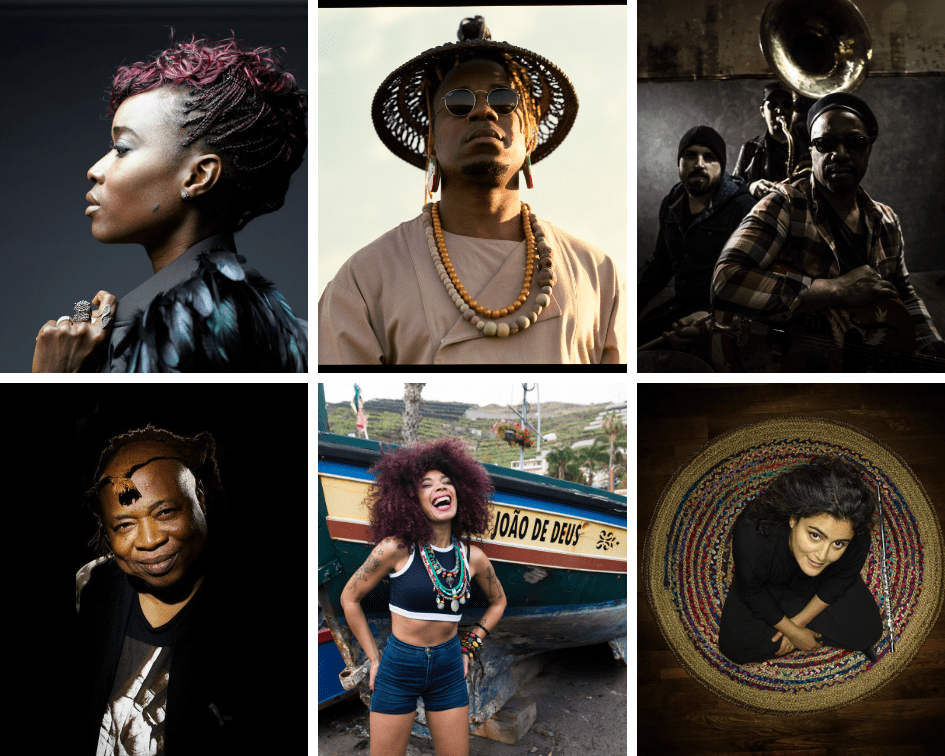

1 - Six artists take sounds of the world by storm

Two years ago, Blick Bassy, Flavia Coelho, Pascal Danaë, Naïssam Jalal, Awa Ly and Cheick Tidiane Seck sponsored the launch of the #AuxSonsCitoyens campaign. We meet them again to discuss the cultural diversity so close to their hearts.

Artists into orbit

If you laid their career paths end to end, they would cover so much of the planet you would need more than a lifetime to explore them all. Despite being based in Rome for almost twenty years now, the singer Awa Ly, born in Paris to Senegalese parents, often travels to Dakar. Her counterpart, Flavia Coelho, a native of Rio de Janeiro, has taken up residence in the French capital after 26 years in Brazil. Originally from Argenteuil, Pascal Danaë took his guitar, voice and Guadeloupean origins with him to London for seven years before moving back to the Paris area. This is also where keyboard player Cheick Tidiane Seck has made his home despite travelling regularly to his native Mali. The guitarist and singer Blick Bassy now lives in Bordeaux after spending time in Paris since leaving his native Cameroon just over ten years ago. Now based in Saint-Denis, the flautist Naïssam Jalal, born in Torcy to Syrian parents, spent time living in Damascus and Cairo after travelling around Mali. It’s enough to make your head spin! Though very distinct, what do these “life itineraries” have in common? They have all been dictated by the same obligation: to spread the word about music and the richness of its diversity. “Artistic freedom has to be completely emancipated from its geographical origins,” says Awa Ly, who would prefer to forget the question she is asked ad nauseam: why does she sing in English rather than Wolof? No one can argue with that. “There are no borders in music,” adds Naïssam Jalal. “There are cultures and vocabularies. But no musical language exists in a vacuum, we can always communicate with the language of others. Better still, if we strive to and want to learn other people’s languages, we can integrate them into our own vocabulary. Sometimes I feel like a polyglot!” A cover singer – jazz, rock, reggae and hip-hop when she started out, blended with traditional Brazilian rhythms – Flavia Coelho is also a polyglot in her way. She claims she relocated to better understand the plurality of her country, built on migration. Fascinated by Paris, a city that offered asylum to so many foreign artists of the past, she quickly found herself confronted by caricatures when she arrived in 2006. “Record companies all said the same thing,” she points out with a smile. “You’re Brazilian, so you’ll play bossa nova, put on a skirt and a flower in your hair, and we’ll sign you tomorrow”. They didn’t know much about someone who has always refused to be confined or straitjacketed. It should be said that plenty of water has gone under the bridge since the advent of world music in Europe in the late 1970s. Its essence and visibility are no longer the same and finding a foothold in the market for a young foreign artist is now a long and winding road.

From Golden Age to crisis

“In the 80s, everybody lived diversity, but no one talked about it,” says Pascal Danaë. “Jazz fusion, or music like it, was played in the clubs. We used to hang around rue des Lombards. The Baiser Salé club was an incredible haven for talent and the place to be for great musicians. It was where I met Francis Lassus, Richard Bona, Minimo Garay, Étienne Mbappé and Hilaire Penda… And some big public hits came out of this diversity, with Cheb Khaled, Youssou N’Dour and Kassav. There was room for this sort of music and a curiosity for what was happening around the world was played on the radio”. Cheick Tidiane Seck beams with nostalgia as he casts his mind back to this period. He was introduced to music theory and the black and white keys of the harmonium by a French-speaking Spanish nun in a Catholic school in Sikasso and lived through the dazzling debuts of La Sono Mondiale – “the worldwide sound system” – as Jean-François Bizot from Actuel news magazine used to call world music. When he set foot in the City of Lights in 1983, he arrived with bags of experience acquired alongside famous orchestras such as the Bamako Rail Band, The Ambassadors and Bembeya Jazz. He went on to write music for some big names on the rock and jazz scenes: Carlos Santana, Joe Zawinul, Stevie Wonder and Public Enemy, to name but a few. “People were much more open-minded about this kind of music back then,” he agrees. “The venues that played host to these artists were generous with their fees and there were plenty of them: the Phil One, the Farafina, the Excalibur… all of which are now closed. As for new venues, most of them have been sanitised”.

We now find ourselves in the dictatorship of a smooth and standardised sound. Large TV channels and public and private radio stations now dance to this tune, drastically reducing the airtime given to diverse world music. Even the metro and the streets no longer offer these artists a spontaneous haven. “There are far fewer concerts in these informal places now,” according to Flavia Coelho. “My first big tour in Paris was on the metro, on lines 4, 7 and 12!” Add to that the stringent laws imposed on foreign artists when it comes to obtaining a visa or a residence permit and the picture can turn into a nightmare for advocates of world culture. “No matter how much we talk about human rights and democracy, we realise that these great concepts have been emptied of their content,” says Blick Bassy. “We don’t have the same freedom of movement today, whether we have an American, German or Cameroonian passport. I have Cameroonian nationality and despite a ten-year residence permit, I have to juggle like crazy, otherwise I can’t work. I need a passport for the Schengen zone and a visa to go to Africa or elsewhere. What do I do when I’m touring in Europe and at the same time, I have to drop off my passport to get a visa for other concerts?” With media coverage down and mobility restricted, our artists have enough to worry about, but not to the extent of giving up. In this hostile climate, they go out of their way to open up new horizons.

From crisis to solutions

In our individualistic society, where the intensification of fear, even hatred towards the Other has become a reality, cultural diversity has more of a reason to exist than ever. It becomes a necessity, a driving force for our artists who promote plurality. “We are all individuals, so we are all different, and we must stop thinking that some people are worth more than others,” says Naïssam Jalal, who gave the name Al Akhareen, The Others in Arabic, to one of the three groups she formed with rapper Osloob. Defender of his language and Bassa culture, Blick Bassy has made his cultural uniqueness the foundation of his music. It is clear to him how sensitive the public is to the imaginary universe he’s built with his music. “Through language, people want to know a bit more, they write to me and ask about the meaning of my texts,” he says. “Beyond music, I’m offering a culture, and this is the reason why our music is so easily marketable. I sell much more internationally than an artist singing in French. I played more than 250 concerts during my last tour, half of them all over the world, outside Europe. It’s an opportunity, a real development strategy”. The same goes for Pascal Danaë, who, with his Creole blues group, Delgrès, has achieved unprecedented public success. “Sometimes I’m amazed by the public interest in what we do,” he says. “The other day, we played near Paris and I met a couple with their children: they had made the trip from Arles to come and see us!” So, the audience is there and venues are often full. To get media coverage, like many of his friends, Blick Bassy calls for change: “We have to break down categories, break free from the ‘world music’ genre we’ve been put in to reach the general public”. This strategy has been applied by his No Format label for the release of his latest opus, 1958. By joining forces with the label Tôt ou Tard, which has a particularly francophone and mainstream catalogue, he can take advantage of a new strike force. When it comes to musical education, the signs of openness also speak volumes: “Plenty of young people from the conservatory are much less conditioned than they were before,” notes Pascal Danaë. “They have a vast culture that ranges from classical to jazz”. Encouraging young musicians to be creative, to take possession of new technologies, to have a precise vision of their project, in short, to be themselves, is an attitude to which our six artists lay unanimous claim.

Raising the diversity flag on all fronts

Blick Bassy, Flavia Coelho, Pascal Danaë, Naïssam Jalal, Awa Ly and Cheick Tidiane Seck are working outside their artistic careers to cultivate this precious multiculturalism. Awa Ly gives concerts for the SOS Méditerranée association that she actively champions; Cheick Tidiane Seck teaches masterclasses in Denmark and the United States, mentors young people informally and sponsors the Ollin Kan Cultures in Resistance festival in Mexico City; Blick Bassy has launched the Wanda-full platform that helps emerging artists master all aspects of the music industry and founded, alongside journalist Elisabeth Stoudmann, the Show Me event in Switzerland, a digital marketplace where international programmers get to meet artists without support structures. As for Naïssam Jalal, she is for many the voice of free Syria and the martyrs of the Revolution. She has dedicated an album to them, Almot Wala Almazala, and performed a number of concerts in support of the Syrian people with her quintet Rhythms of Resistance. However, she’s opposed to the idea of being an ambassador: “We cannot separate a person from their influences, world or imagination, nor can we reduce them to that. They have their own language. I only represent myself”. Except Naïssam Jalal pushes the boundaries back so far that she sometimes ends up being the Other. With this in mind, she tells this wonderful anecdote, laughing out loud: “One day, I recorded a piece for the African Vibrations album by Sébastien Giniaux and Cherif Soumano. At the end of the session, one of Cherif’s friends – who had been listening outside with amazement – asked him who the musician playing the peul flute was… Noticeably proud… It was me, a French girl with Arab roots, on her transverse flute!”