Narcocorridos (Drug Ballads) are perhaps one of the most controversial contemporary musical genres. Their apparent traditional simplicity can easily mislead the ingenuous listener unfamiliar with its history and the complex social realities that surround it.

Indeed, its detractors label it as murder music that romanticizes narco culture, because it celebrates the deeds of drug lords and promotes violence. The fact that musicians themselves have been often closely associated with the cartels and even murdered through cartel rivalries, has only contributed to increase this stigma.

On the other hand, its listeners see it as an offspring of the traditional Mexican corrido, which has undergone several transformations throughout its history until arriving at its current, brutal form: Corridos alterados (Altered Corridos).

Narcocorridos tell a harsh unofficial truth. This music unveils the life of criminals and mirrors the violent reality that Mexico has suffered in the past decade, especially after the war on drugs was launched by President F. Calderon in 2006 and the country reached unprecedented levels of violent deaths.

Despite multiple attempts to ban this music in various Mexican states, narcocorridos are more popular and radical than ever, with growing audiences both in Mexico and in the USA, especially among the Latino diaspora.

How is it possible that people enjoy songs that sing of drug lords and violence after the ongoing war on drugs has left, according to a 2019 USA Congressional Research Service report, more than 150,000 dead in Mexico?

Between tradition and modernity:

Corrido music has not been historically associated exclusively with drugs and thus also has legitimacy as a traditional music form. In fact, several Mexican states such as Durango and Chihuahua have corridos as their un-official anthems and many Mexicans proudly endorse them.

The Mexican golden age of cinema (1933-1964) produced a large quantity of musical films that projected the nation to the world with its traditional ranchera and corrido music. Many of these films attempted to articulate a true national identity and not only shaped how the world saw Mexico but also marked the Mexican imaginary and how Mexicans saw themselves and their history.

The narcocorrido added new themes such as the life of poor migrants in the USA, with their hardships and adventures. The life of legendary singer Chalino Sanchez epitomizes this phenomenon. His tragic death resonated with thousands of Mexicans who identified with him through their shared experiences of struggle with poverty and migration to the USA. He was also the first of many other corrido singers to be murdered, including Valentin Elizalde in 2006.

Under the guise of the traditional corrido form, the narcocorrido represents a hybrid of traditional folklore and modernity, rural and urban culture, Mexican-American frontier culture and of official and subversive values.

Multiple factors have transformed the Narcocorridos

The Mexican war on drugs, the emergence of Mexican-American entrepreneurs catering to a growing American audience, along with new digital technologies and the visual influence of violent music videos such as Gangsta rap have completely transformed the narcocorridos in recent years.

Attempts to censor this music in Mexico by banning concerts have failed for several reasons. The audience has changed, and Mexicans are no longer the only ones listening to this music. It’s a very organized industry that generates millions of dollars. For instance, the Movimiento alterado merchandizes clothes, films, concerts and clips of the movement. Their tours include performances in several cities in Mexico and the USA with tickets sold by the giant of ticket distribution: Ticket master.

Production, distribution, and consumption have radically changed in the music industry. They are now generated via digital strategies that the new generations of musicians have used effectively. A few clicks on YouTube suffice to find a large repertoire of videos showcasing armed criminals with all the stereotypes associated with mafiosos that have “made it”.

A case in point is ”Los sanguinarios del M1”, posted in 2011 and with over 53 million viewers to this date.

The entertainment industry now produces films and series such as Narcos: Mexico, El Chapo, and Escobar, which have also contributed to the popularity of narco culture. They have contributed to legitimize and mainstreamize a popular musical niche with more extreme and explicit violence.

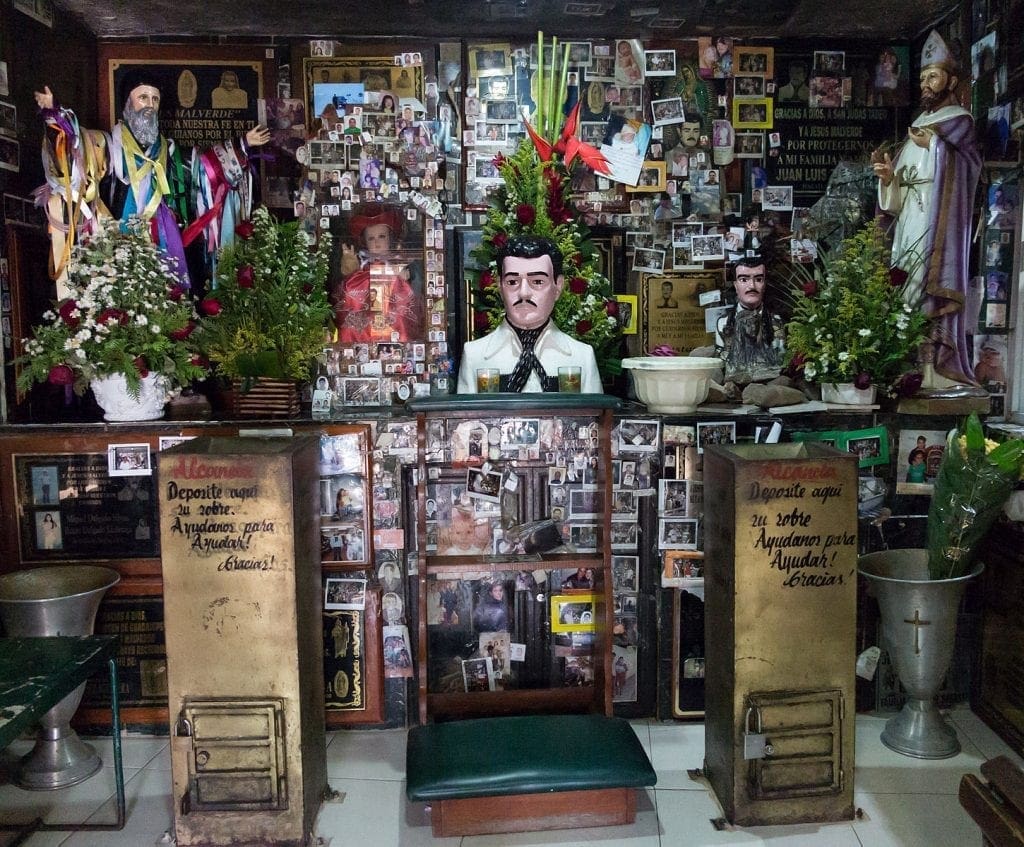

Narcocorridos are also part of a broader culture and diverse social practices. In Sinaloa for instance, the cult of Jesus Malverde, a folklore hero from the early XX century is worshiped as a patron saint of drug dealers. Malverde’s shrine is regularly visited by thousands and his images are reproduced on all kinds of objects. Narco cemeteries such as Jardines del Humaya in Culiacan contain some of the most lavish and glamorous mausoleums in the world. These practices reveal the macabre relation to death that haunts most narcocorridos.

To some, the mix of tradition and contemporary violence signal attempts by Mexican society to come to terms with the world around them. To others, they are simply a perversion of a music tradition. Although intimately related, narcocorridos can’t be entirely blamed for drug violence. Drug violence is to blame for narcocorridos. These songs are very popular in Mexico but are also a phenomenon found in other drug-ridden countries in Latin America.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, one of the most shocking aspects of the narcocorrido, is that it no longer seems to shock anyone. In any case, it constitutes a brilliant sociological object that allows us to observe the contradictions of Mexican contemporary life and its attempts to make sense of the social ills that roam in the country. But more importantly, they force us to take a hard look at the inescapable violence of Mexican reality.

By the same author : « For a new awareness of music listening »

« Modern urban troubadours : Beggars or buskers ? »

« Portraying the city through music »