On Sunday evenings in the bars of Brazzaville’s Bacongo district, Congolese rumba and Sape become one. Against the soundscape of music playing from walls of speakers, members of the informal Société des Ambianceurs et de Personnes Élegantes [Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People] walk through the crowd with studied nonchalance, strutting as they show off their clothes. Meanwhile, singers and musicians such as Papa Wemba – the Kinois (resident of Kinshasa) in furs – have blended rumba with Sape. But this link is not new: in the mid-19th century, immediately after the return of the Europeans, the Congolese seized upon and reinvented the world forced on them.

The frock coat, accordion and gramophone

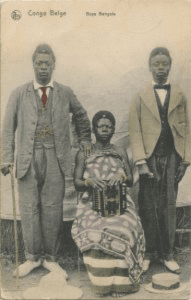

“Belgian Congo. – Bangala Boys”, postcard, circa 1905. © Manuel Charpy Private Collection

Even before colonisation, the kingdoms of Kongo and Loango were connected to the Atlantic region through slavery, West Africa through trade and Europe through traders and missionaries. But it was not until the 1880s – with the setting up of factories and colonial administrations – that powder, copper, brandy and what are still called “trade goods” (fabric, sewing machines, old clothes, accordions, guitars, etc.) arrived in large quantities. These “barter goods” were used to take possession of land, ivory and rubber. Clothing quickly became the focus of relationships between colonisers and the colonised. The myth of the “noble savage” overshadowed the splendour of the Kingdom of Kongo in such a way that clothing manufacturers saw the Congo as a market waiting to be conquered[1]. The trade in fabrics and second-hand goods did indeed flourish, but merchants were surprised to discover that the “natives” had taste and preferred clothes made in Paris – sometimes ordered by post – to what they referred to as “cheap tat”.

Christian missionaries imposed European clothing on them to cover their bodies in a decent manner. Students were dressed in uniforms and “Christian weddings” were celebrated dressed in the European style. Clothing denoted the bodies of those who had been converted, like a flag on conquered land. The “civilisation” of bodies also involved the harmoniums and gramophones that punctuated Christian life.

As clothing and music became political and social markers, local chiefs got hold of used suits, introduced the accordion into royal music and covered their tombs with umbrellas and hats [2].

From the end of the 19th century, these “chefs de pacotille” (tacky chiefs) or “chef d’opérettes” (operetta chiefs) were mocked and “savages” caricatured in frock coats and top hats with bare legs and feet. Sarcasm also focussed on the “nasal melody” of the accordion and the “cacophony” of religious and military fanfares. For Europeans, the natives clumsily “aped” the colonisers.

“Danses à la cité indigène” [Dances in the indigenous city], 3 December, 1922, photographed by a settler in Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo). © Manuel Charpy Private Collection

Sidestep

But from the 1900s onwards doubts began to set in. The colonial powers were worried about these defiantly elegant houseboys, workers and administrative employees. White shoes, panama hats or colonial helmets, waistcoats and pinned ties became subversive. Were these “negroes” better dressed than the settlers? Refinements and melodies threatened to undermine the hierarchies and foundations of colonisation, especially as male bodies were at the centre of the political game. In neighbouring Angola, carnivals at which people dressed up as Portuguese settlers were banned. The “natives” also manifested their refusal to be a colonial labour force in this way. In Tintin in the Congo (1931), the reader can only laugh at the Congolese man wearing a boater, cuffs and tie, who refuses to work for fear of getting dirty.

The police scrutinised these dandies, especially as they seemed to have joined forces with the anti-colonialists, including Matsoua’s spoof Société de l’Étoile des Savoyards de Brazza [Society of the Savoyards Star of Brazza]. The investigators stressed “the attitude taken by a certain category of natives in their immediate relations with Europeans: no external deference to the agents representing authority, and […] a kind of perpetual sneering from the workers”. There was concern about the influence of anti-colonialist ideas on “this sort of elite […], of which there are many who live largely in Brazzaville, imitating our ways as closely as they can, dressing richly if not with elegance, [using] the rarest if not the most appropriate terms”. As well as worry about these brains that functioned like “gramophone records”[3]. The administrations were so ill-at-ease that they tried to promote the most “advanced” natives to assist them, instilling them “good manners” when it came to dressing and mastery of the French language.

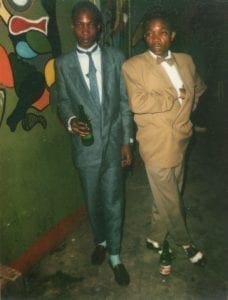

By the 1920s, this “elite” of administrative employees, houseboys and “literate unemployed” were organising themselves in clubs around fashion and music. Encouraged initially by the administrations, they became more common in Brazzaville in the 1950s and 60s: the “Existos [Existentialists]”, “Les élégants inégalables [The incomparable dandies]”, “Simple et bien [Simple and good]”, “Club des Six [Club of Six]”, etc. Each club had its own codes, but everyone would dress in ready-to-wear to distinguish themselves from the population dressed by local tailors. They exchanged clothes so they would not have to wear the same thing twice and talked about fashion.

Séverin Mouyengo parading in Bacongo, early 1970s. © Séverin Mouyengo Private Archives / Digitised by Manuel Charpy

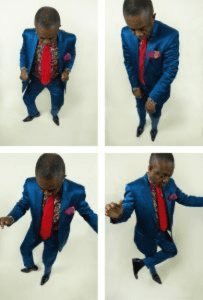

From the 1900s, young people gathered in “tam-tams”, to use the colonial term, to dance to the sound of percussion instruments, accordions and guitars. In the 1920s, the fashionable dance, the agbaya[4], was performed in a circle to show off dancers’ clothing - like the “danse des griffes” [literally, “logo dance”] of today’s Sapeurs. But as early as 1904, the administration banned these gatherings except on Saturdays. The segregation of Brazzaville and Leopoldville into “indigenous cities” and European neighbourhoods solved the issue by banning the mixing of populations in the evening[5]. From then on, fashion and music mingled in Poto-Poto, Bacongo and Matonge every Sunday.

Simmering under the surface

Despite discrimination and curfews, both cities teemed with international influences during the 1920s. Goods would come from all over the world: wax cotton from The Netherlands and Manchester, ready-made and used clothes from Paris, helmets from Marseille, shoes from Japan… Tailors were known as “Fayettes” because they copied department store catalogues, from Galeries Lafayette in particular, and fashion magazines. Paris fashion was “exasperated” by the dandies.

Dance clubs run by Greeks and Portuguese, at the margins of power, made residents boogie, alongside returning infantrymen, Europeans passing through and West African workers, among others. People would strut in fine dress to the rumba. Rumba was finding its way back – having been carried away by the Kongo slaves - from the Caribbean through West Indian soldiers stationed in Brazzaville, bands performing on both banks and records. In the 1930s, it was listened to alongside the Charleston at colonial festivals - street markets, beauty pageants, Bastille Day celebrations, races - much to the dismay of the religious authorities[6]. The locals played maringa and palm-wine music - originally from Ghana, remixed with guitars brought by West African workers and, increasingly, rumba. As gramophones were everywhere, 78s made this music popular. The dandies’ soundtrack was a mixture of traditional music played with European instruments, religious choirs and music from the Caribbean. The Sapeurs made this way of mixing cultures, including colonial ones, their own. Was there a touch of irony when the “Gallo-Roman” club founded in the 1970s announced: “Come and taste Spanish rice, Brazilian “brede”, English chicken, French cassoulet, Dutch omelette and Italian spaghetti. Weston shoes required”? And continued: “For more than 400 years, the Gauls imitated the Romans. They got used to their way of living and learned their Latin language. Gradually, you could no longer tell the difference between them and the inhabitants of Gaul were all called Gallo Romans.” [7] Melting pots can be subversive.

Down with the suit!

The Logo Dance by Bachelor © Photo Pablo Gran-Mourcel, Kevin NGomsik, Manuel Charpy

It should be said that as far as Sape was concerned, independence did not herald a golden age. The success of rumba came from the fact it was both danced and played by those who were well dressed, Rochereau or T.P. OK. Jazz, for example. But Sape was not as politically malleable as rumba. Untouchable in its popularity, it lived through successive regimes seamlessly. In Brazzaville, the founding of Radio Brazzaville by De Gaulle in 1940 promoted its spread. It wasted no time becoming the music of independence then that of every regime, from N’Gouabi - of Soviet-Cuban inspiration -, the communist Sassou N’Guesso to Mobutu, the herald of “authenticity”. It glorified the achievements of power just as it did haute couture brands.

On the other hand, Sape was seen as a servile imitation of the former colonisers. In Brazzaville, after the fall of dictator Dior Fulbert Youlou in 1963, the new single-party regime led a Chinese-style revolution. The Youth of the National Revolution Movement came to blows with the Sapeurs, ripping their clothes, and they were “rehabilitated” in the countryside by the regime. On the opposite bank of the river, Mobutu’s “Zaireanisation”, launched in 1971, went after the Western suit, replaced by the “abacost” (from the French “À bas le costume” [Down with the suit]), a kind of short-sleeved Mao jacket.

Bachelor (Jocelyn Armel) out one evening in Paris, 1970s. © Jocelyn Armel archives / Digitised by Manuel Charpy

While young people in Europe and the United States abhorred the suit and tie, it became a sign of distinction and dissent in both Congos. Sape’s migration to Brussels and especially Paris, a fashion pilgrimage, was therefore understandable. But in the eyes of these societies, immigrants were a workforce that was supposed to save money and be discreet. But Sapeurs lay claim to their refusal to be assigned to physical work through their elegance, rejecting savings made by workers and making themselves visible in the public space.

By digesting exotic cultures, the Congo reinvented rumba and Sape, two long-standing products that have nothing to do with subcultures, in turn exported all over the world.

[1] Described by Charles Lemaire, Au Congo : comment les noirs travaillent [In the Congo: how Blacks work], Paris, Bulens, 1895, p. 104.

[2] Alexis-Marie Gochet, Le Congo français illustré : géographie, ethnographie et voyages [The French Congo Illustrated: Geography, Ethnography and Travels], Paris, Procure Générale, 1892 and 28 années au Congo : lettres de Mgr Augouard [28 years in the Congo: letters from Mgr Augouard], Poitiers, Augouard, 1905.

[3] National Overseas Archives, Police Report, Brazzaville, 1930.

[4] See the seminal book by Phyllis Martin, Les loisirs et la société à Brazzaville pendant l’ère coloniale [Leisure and Society in Brazzaville during the Colonial Era], Paris, Karthala, 2006, p. 177 et sq.

[5] See Georges Balandier, Sociologie des Brazzavilles noires [Sociology of Black Brazzavilles], Paris, Armand Colin, 1955.

[6] L’Étoile de l’AEF, [The Star of the AEF], December 1933. This music is described as “blues” by the commentator.

[7] Invite card collected by the sociologist Justin-Daniel Gandoulou; see his essential investigation: Entre Paris et Bacongo [Between Paris and Bacongo], Paris, CCI / Georges Pompidou Centre, 1984.