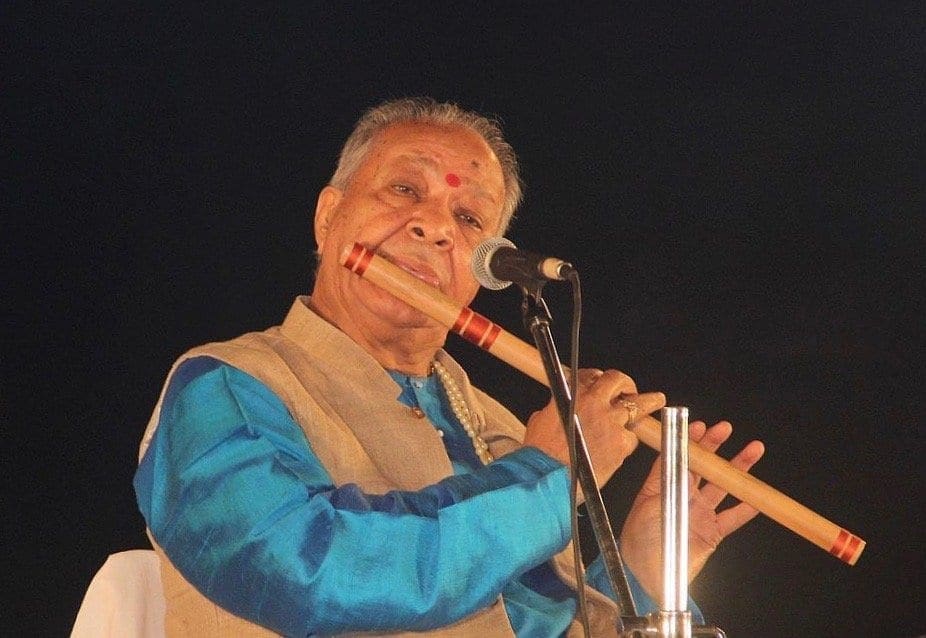

Hariprasad Chaurasia, Danyel Waro, Joyce, Ray Lema, Zakir Hussain…they may all be giants of the music scene, but they also belong to a group considered “at risk” during the current health emergency. At a time where the elderly are quarantined, we address the elder statesmen and women of the musical tradition.

Hariprasad Charasie/Zakir Hussain

He got up at dawn like he does every morning. He freshened up, did a few stretches to get things moving then gave thanks at the little temple in his courtyard. For the rest of the day, in the open-air school in which he is quarantined, he played the flute. On the 1st of July, Hariprasad Chaurasia will celebrate his 82nd birthday; he isn’t just a musical maestro, he’s a national treasure. He doesn’t bat an eyelid when he tells you about the day his mother died, when he was six years old; he still remembers her lullabies. He also tells you about when, as a teenager, he found a teacher, Rajaram, who taught him to sing. “I urgently needed a guru”.

Hariprasad Chaurasia now stands vigil over his own gurukul, his academy, in Bombay. “There are only five of us during the pandemic. They take care of me; we take care of each other”. He’s not a fan of online courses: “I want to hear the sound, tempo, intonation perfectly. It’s not just about playing; it’s about being there for each other”. Chaurasia has recently witnessed the exodus from the megalopolis in which he was born, migrant workers returning to their home villages to escape the lockdown. He has seen the world change. “When the elderly die in numbers, it’s an ineffable loss”.

For weeks now, we’ve been describing the elderly as an at-risk group, the refrain creeping in from a world that has stopped protecting humans who are “unproductive” and have already lived their lives, in danger of widening the generational divide forever. Imagine, we’ve even talked about confining the over-65s to their homes for months or perhaps years, wanting grandparents not to be able to hug their grandchildren anymore.

The lightness with which we’ve considered depriving ourselves of the elderly in the hope of saving them, of saving US, says something about our society as a whole. It overlooks the role played by the older generation and the very idea of knowing how to pass things on.

Danyèl Waro

From his home, Danyel Waro can take in the Baie de Saint-Paul, where the pebbles end, and Cap La Houssaye. He lives in a kind of savannah, on Réunion: “We began squatting here 16 years ago. There weren’t many people”. They built a little alternative school, where it was as much about planting as counting, a school of Creole and the land: “You have to be rooted, standing up, proud and calm. We don’t have our tree in our textbooks, our lifeblood, our way of believing. The books are centralised, they deal with French culture, autumn and winter, seasons that don’t exist here. This turns our kids into foreigners in their own country”.

When he was 15 or 20, Danyel Waro was angry. “My father drank. He would shout. The tree of drunkenness hid the forest of learning and tough, austere affection. But he still showed me the fields”. Waro found other guides: Paul Vergès, Firmin Viri and Granmoun Lélé. “They taught me to go beyond the confines of my language, my culture. You can’t separate the old from the young”. When he sings maloya, Waro, aged 65, shakes his kayamb like a boxer (a rattle shaped like a raft, it makes the sound of rain and the harvest).

It is, for its island, not just a spring, but an estuary. It is continuity and renewal.

Ray Lema and Manu Dibango

This idea of tradition handed down like tectonic plates that separate, brush against and sometimes smash against each other is embodied perhaps better than anyone by the Congolese composer Ray Lema. Covid-19 has robbed him of his brothers: Tony Allen and Manu Dibango. He quotes the well-known phrase by the writer Amadou Hampâté Bâ: “Whenever an old person dies, a library burns down”. Ray, who is feeling really blue, has to focus to do his scales in the morning. “I don’t go out much. I’m doubly at risk: I’m 74 and I have asthma. We’re being told to wear masks and gloves whenever we go outside”.

Ray had decided to become a priest; he entered the seminary at 12 years old. His musical skills were spotted so the White Fathers sat him behind an organ. It was there that he learned Gregorian. Then he was given an upright piano from Belgium. He studied Chopin, but also slipped into African independence songs, rumbas, drumbeats and jazz. Ray Lema did not choose between the different schools he came across, so ended up founding his own.

“It was very bad for business. Record dealers never knew where to put me. They thought I wasn’t ‘world’ enough, but I come from the world! Whenever a young musician comes to see me, I ask them what their motivation is. If they just want to be famous, I tense up. The most precious thing that can be passed on is this freedom”.

Angélique Kidjo

The same sentiment is felt by Angélique Kidjo, who answers our questions between baking loaves. “I can’t sit still, so I’ve been cooking during lockdown!” She was supposed to be creating a new show at New York’s Carnegie Hall these last few weeks, a tribute to black independence, with Manu Dibango and American singers. “I was born in 1960, just before my country, Benin, became free. I had invited American singers to do this show to celebrate civil rights as well. You know, one of the merits of getting older is that you don’t really care if you don’t look like anyone else”.

Joyce

A few thousand miles away, in the south of Rio, the singer Joyce, aged 72, looks forward to banging her pots and pans at the window every night. “This is how we express our disapproval of Bolsonaro. Most people shout too, but I’m trying to save my voice”. Joyce grew up in Ipanema; her teenage friends were Tom Jobim, João Gilberto, and Elis Regina. She whispers sweet, revolutionary words in a nation that is inventing itself: “Bossa nova is Brazil the way it was supposed to be”. She was a feminist before the rest of her generation; she was emancipated, humming, with such a sophisticated guitar that people would come to take lessons from this self-taught musician.

“Nowadays, whenever young musicians come to tell me that I’ve inspired them, I pretend like it’s nothing, but it’s really touching. I’m also the daughter of other women. We’re links in a chain of emancipation”.

“How long will I continue to strum chords?” gasps Laurent Aubert from his den in the Geneva area. “My mother has just turned 93 years old”. He has founded the Ateliers d’ethnomusicologie (the ethnomusicology workshops - ADEM), a reference in the world of traditions, and he is taking advantage of his retirement to get back to the Afghan, Turkish and Arab lutes. « It keeps me busy. » Aubert tells us about his own teacher, Daoud Khan, who is younger than him and who has put him back on tracks. « I stopped playing for 30 years. I feel like I’m picking up music where I had left off. »

Laurent Aubert mentions cleanness, depth, qualities he often found in elderly Maestros. “I could speak of vivid memory. In some elders, there is an incalculable number of musical data that can arise at any time”.

Zakir Hussain and Alla Rakha

This is precisely the feeling we get when listening to Zakir Hussain. We want to address him at the end of this immobile report in the land of those who have lived and keep on living. He has been for so long the embodiment of juvenile energy and cosmopolite appetite, that it is hard to imagine him celebrating his 70th birthday soon. Zakir is the son of an immense Indian musician, the percussionist Alla Rakha, who has contributed to the definition of his instrument (the tablas), but who has also opened up classical music from Northern India to new winds, such as drummer Buddy Rich’s jazz for instance. Mickey Hart from Grateful Dead described him as an Einstein and a Picasso of rhythm.

Strangely, Zahir Hussain has never felt burdened by this heritage. He telephones from his house in Sausalito, in front of San Francisco, he describes the pure air, the roads deserted by cars, all the merits of a global slowdown: « In 2019, I lined up 5 different tours. 50 concerts in spring, 30 in the summer. Honestly, I hadn’t even realised how much I had been sunken in work these past years. I am honouring this pause. »

In each of Zahir’s sentences, we can feel the mark of his teachers. Ravi Shankar. Ali Akbar Khan. John McLaughlin. And his own father: « He told me I should remain a good student throughout my whole life. When someone would tell him he had given a perfect concert, he would answer that he hadn’t played well enough to give up music quite just yet. »

At a young age, Zahir took off to the United-States with Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, the sarod lute player. « He never addressed me as if I were a child. He called me Sir. I never felt anything else but the respect granted to a disciple doing his best. I always had the feeling I was playing with musicians more talented than me. And still today, when I hear the young Indian musicians, they are so incredibly talented. It’s frightening! I am learning more from them than what I am actually teaching them. »

During lockdown, Zahir Hussain hosted Instagram sessions. « It’s important to pass on what we know, to disseminate the information. When the bodies are at distance, it’s the only available means of communication. Even when confined, we are not alone. We must avoid at all costs breaking the links of transmission. »