When we talk about Creole culture, we have to look past plenty of concepts and ideas inherited from “vertical” cultures. In Europe, Africa and Asia we see that physical type, territory, language, law, music and cuisine are usually in perfect geographical coherence. On the other hand, in the Creole world, identities come about thanks to an unpredictable interweaving of heritages.

A French Antillean – in other words, a native of America – may have black skin from Africa, speak a European language with its baggage of literature, legal concepts and religious convictions, cook food influenced by Asia (rice is ever-present and the “national” spice of Guadeloupe is called colombo) and listen to everything that is happening musically around their region on a daily basis.

Perhaps it is easier for a French-speaking Antillean-French Guianese music lover to admit the complexity of their heritage than for an artist, more easily subject to being assigned to a particular genre or style and often bound by requirements of purity to which no one would even dream of subjecting their audience. A French Antillean will therefore gladly assume a place at the crossroads in which they find themselves listening to Spanish-speaking music (bolero from Cuba, salsa from Central America or merengue from the Dominican Republic), the vast Cuban heritage, so-called black music from the United States (from jazz to funk and rap), reggae from the north of the West Indies and calypso from the south, French chanson in the broad sense (from “Au clair de la lune” to Aznavour and PNL), all the successive waves of international pop… and, of course mizik an nou.

Mizik an nou [our music] is music subject to a dual search: on the one hand, for an identity that distinguishes it from that of other regions, and on the other, the search for a cultural and commercial relevance that ensures the influence of these three French possessions in the global concert of popular music.

The French Antillean-French Guianese proudly flaunt their biguine, gwoka, bélé, kaseko and zouk. But we must remember that they also sing dancehall and “Le plus beau de tous les tangos du monde”, play jazz, bossa nova, steel drums and kompa with the colours, fragrances and freedoms that belong only to them.

The only Caribbean territories still under French sovereignty are Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guiana, Saint-Martin and Saint-Barthélemy. But plenty of other territories have at one time also been French (Haiti, Saint Vincent, Dominica, Saint Lucia…) or are under a lasting French cultural influence (Trinidad and Tobago, parts of Cuba) and it would not be surprising to find obvious similarities (notably the use of French-speaking creole) in musical forms considered to be specific to Anglophone areas.

French Antillean music is sometimes presented solely through the prism of the professed skin colour of its performers. Some are said to be plainly “black”; others more “mulatto” or mixed. In either case, it is to knowingly ignore the crucible of Creole cultures – a human cataclysm of appalling violence but astonishing fecundity.

European attempts to create a New World by sending in settlers, soldiers, convicts and all kinds of poor wretches driven out by misery, arbitrary royal power, justice and religious persecution were a long litany of failures, tragedies, unnecessary wars and sanitary disasters, in the wake of which cities, ports, trading posts and even nations were built.

As the enslavement of the Amerindian populations could not be sustained over the long term, the use of the African slave market became substantial. In the course of the three centuries of the Atlantic slave trade, followed by a few decades of slavery in the American colonies despite the enforced drying up of the source of “ebony”, societies were founded on the strict distinction between races. But the opposition between white slave traders and black slaves does not sufficiently describe the situation on these islands. An extremely complex grammar of interracial relationships and infinitely subtle gradations between humans of different interbreeding and status would structure these societies.

Nor are drums hit by bare hands and surrounded by rudimentary percussion instruments the preserve of slave resistance music or the pride of maroons - the runaway slaves. It seems that their origins are much more complex, paradoxical even.

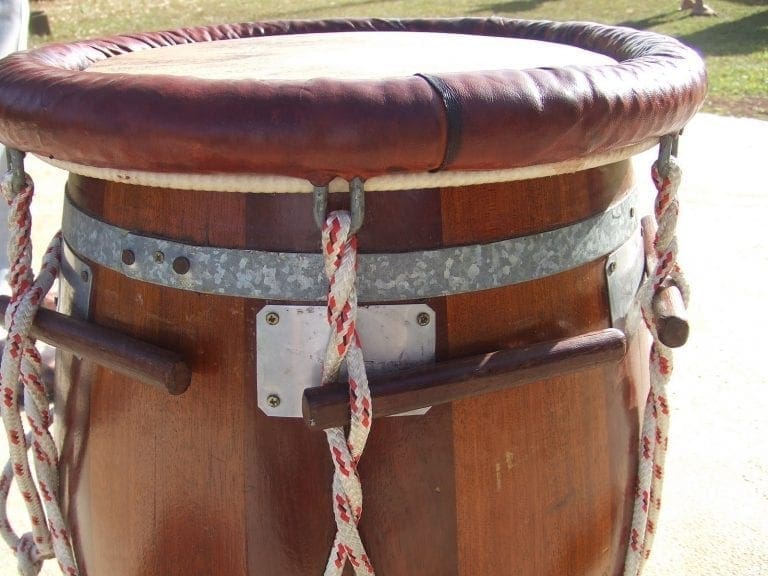

Slaves were forbidden to cut down trees, so were unable to make hollowed out wooden drums. Conversely, the use of old barrels was tolerated: the name gwoka, drum-based music from Guadeloupe, comes from “gros quart”, literally “large quart”, used to contain salted meat and salvaged to make drums. Several rhythms linked to working in the fields, levelling earth and, in particular, to the cutting of sugarcane remain in the collective memory, demonstrating that drums were also an instrument of oppression, intended to provide a tempo to slave labour.

After the abolition of slavery in 1848, this music began to circulate more freely, especially among those living in the countryside and suburbs, swelled briefly every year by carnival crowds. The gwoka from Guadeloupe, the bélé from Martinique and the kaseko from French Guiana – each with their own particular features in terms of instruments, choreography and sociability – had decisive points in common, including a dual function as dance entertainment and critical expression.

Lyrics were always deliberately concise, but always included choruses ideally sung by all those assembled. This music evoked social themes: the expenses of life, the hardness of work, the infidelity of women, the hassles of public transport, the changes of technological progress, a natural disaster, the crush of the city as it appears to someone visiting from the countryside, and so on.

During social conflicts, strikes by agricultural workers in particular, this drum music sometimes carried with it slogans but, overall, was low intensity in terms of its politics, but could be played with meaning and great power. To use the Creole expression, this was mizik a vié neg – not the music of old black people (vieux nègres) in the sense of age, but dirty, insignificant and despicable black people. This music would gradually come to be considered as the sign – and even the admission – of exclusion. Modern French Antilleans had to become civilised, wear shoes or sing in French, and playing a drum was seen as a sign of backwardness.

In the 1970s, the bélé from Martinique almost died out and survived only in a folklore form or in its “natural” state in remote areas to the north of the island. There was a major symbolic victory for the Guadeloupean cultural revival movement in the early 1980s when drums became a part of daily life in Pointe-à-Pitre and left the suburbs to settle in the city centre every Saturday morning.

This music remained in use locally but was unexportable globally in its vernacular form, which, nevertheless, has gradually imposed itself over recent decades as proof of the daily musical landscape of the Caribbean’s French territories.

This was not true of biguine, which, very early on, was a music of mass export, a phenomenon that deserves to be underlined as it became a small empire. Biguine emerged primarily in Saint-Pierre, economic capital of Martinique, a port exporting rum and sugar. It was mainly a creolisation of polka, a dance rhythm from the city that dominated in the salons of the affluent classes and moved into the venues and celebrations of the working classes in a relatively small city of around 25,000 inhabitants.

But biguine was not simply a mutation of polka. The new form incorporated locally generated rhythmical patterns, blending cultural debris of African origin (the transatlantic slave trade was abolished in 1815), most likely revived by the arrival of African contract workers in the wake of the abolition of slavery. In its functions, it takes on the polysemy we find in French chanson, alternating or even combining recreational elements with the seriousness of the subject. Given that polka was, at that time (in addition to waltz), the dominant rhythmical form in urban commercial song at the advent of the 20th century certainly supports the variety of roles assigned to biguine.

Biguine sang of love in all its varieties, the anecdotal and immediate history of society (including a significant production of electoral biguines) and, very quickly, it began to build a significant nostalgic repertoire. Biguine has something akin to tango, Creole music from Argentina, and French chanson: its ability to sing about itself, while celebrating the good old days. In the case of Martinique, the destruction of Saint-Pierre would clearly link biguine to the myth of a lost paradise, without depriving the music of its relevance in the here and now for several generations.

In a way, biguine was strengthened in its original areas by the fact that it was easy to export. The period spent in France in the 1930s by clarinettist Alexandre Stellio and singer Léona Gabriel, followed by a large number of artists who had spent varying lengths of time outside their country (Sam Castendet, Félix Valvert, Gérard La Viny, Robert Mavounzy, Ernest Léardée, the Coppet brothers, etc.) contributed not only to the contagion of a great many musical forms in Europe and North America by biguine, but also to its conservatism in the Caribbean. A musical standard-bearer for the French Antilles, biguine would continue to evolve between innovations (the invention of biguine wabap, the compelling evolution of instruments, etc.) and the need to remain unchanged. The international success of biguine did much for its local preservation, obviously more successfully than that of the mazurka or quadrille, musical forms of European origin spectacularly creolised during the 19th century.

We might also consider zouk – born in Paris in the early 1980s – as a synthesis of drum music and biguine, had so many other elements – kompa and kadans, originally from Haiti, funk, salsa and FM rock – not become part of its genesis. A laboratory product invented by Pierre-Édouard Décimus, Jacob Desvarieux and Georges Décimus, three Guadeloupean musicians, zouk uses a basic rhythm from the Pointe-à-Pitre carnival, the mas a sen jan, blended with modern musical and efficient shades borrowed from other genres.

The worldwide popularity of Kassav’ has confirmed the relevance of its founders’ intuition. Driven by the diversity of its singers, zouk by the group from Guadeloupe and Martinique would encourage several generations of artists to take up, diversify and systematise the genre, while African urban music was in turn profoundly transformed, the first “return trip” in history, according to an expression used by a member of Kassav’.

The hegemony of zouk was eroded in the 2010s, thirty years of absolute rule giving way to the influx of hip-hop productions or those inspired by new international pop. Zouk finally took the place of biguine in the 1960s–70s, a cultural pre-eminence felt with a full dimension of identity. And, in the same way, the French Antilles strengthened the perception of their own truth through their music’s international audience. But, once again, the condescension of cities towards these regions prevents this success from fully emerging as a cultural victory.