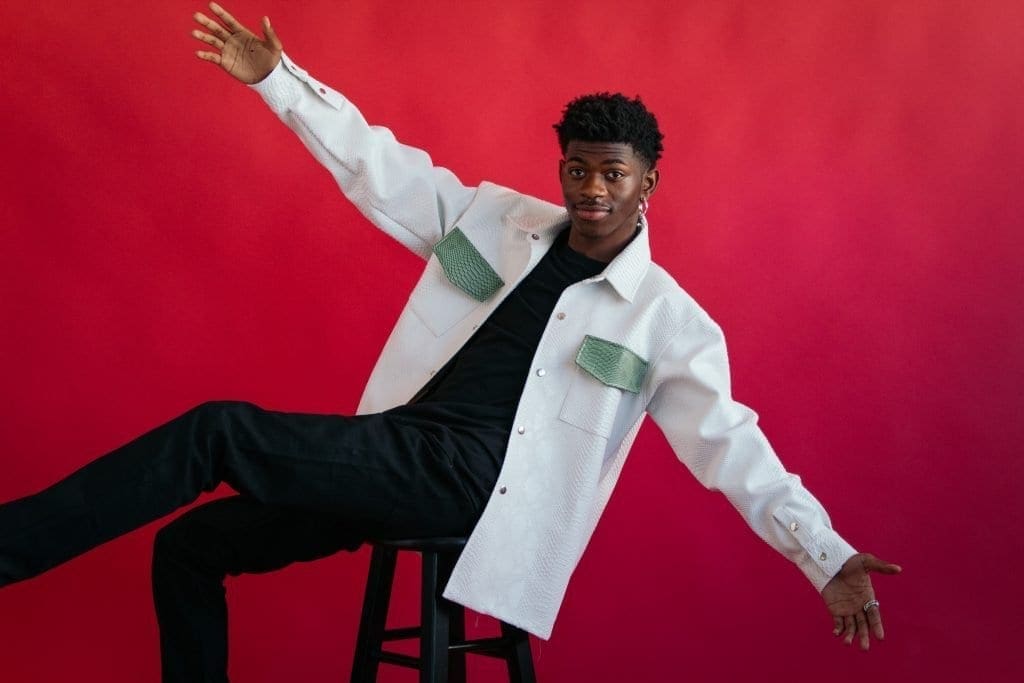

At the recent Grammy Awards, the rapper Lil Nas X began by walking the red carpet in a candy pink cowboy outfit, before performing his hit “Old Town Road” with the country singer Billy Ray Cyrus. The 20-year-old gay African-American had been the subject of controversy a year earlier when Billboard had removed the song from its Hot Country Songs Chart – in which it was 19th at the time – on the pretext that it “does not embrace enough elements of today’s country music”. Mixing elements of trap (bass) and country (banjo), the song still broke the record for the number of weeks at the top of the charts, previously held by Mariah Carey. In spite of that, the song did not make it back to the country music family fold, famously described by the singer Harlan Howard in the 1950s as breaking down to “three chords and the Truth”.

The “Old Town Road” affair is not innocuous in an American society constituted by racialisation. Since the 1920s boom – in the context of the segregationist Jim Crow laws – and as recently as the late 1940s, the music industry even categorised as “race records” all blues, jazz and gospel targeted towards African-Americans, whilst country music – then labelled “hillbilly music” – was implicitly addressed to a white audience. This demarcation is still fixed in minds and facts, a century later. Apart from the absurdity of its precept, it has no historical basis, as hammered home by Rhiannon Giddens with the erudition of an ethnomusicologist at all her concerts. Born in North Carolina to a white father and a black mother and author of the wonderful album There is no Other with Francesco Turrisi in 2019, the singer also plays the banjo, an instrument whose origins, she reminds us, are African (its ancestor is the akonting, a West African lute). Combined with the 19th-century violin by European colonists, who themselves imported various traditions, the banjo is an important factor in the original creolisation of North American music. “Musical and cultural ideas have been crossing over forever”, Rhiannon Giddens told The Guardian. “My projects are all going towards the theme: ‘We’re more alike than we’re different’”.

Country Music, the recent at length documentary (16 hours) by Ken Burns featuring Rhiannon Giddens, was broadcast on PBS at the height of the Lil Nas X debate. It tends, above all, to show how the “white” industry has done away with the “black” roots of spirituals and working songs. In the South, exploited whites and oppressed blacks rubbed shoulders with the same misery in which cultural porosity was at work. For example, Ken Burns shows that the black gospel song “When The World is On Fire” became “Little Darling, Pal of Mine”, a country hit for the (white) Carter Family in 1928, then “This Land is Your Land”, a folk anthem by Woody Guthrie in 1940. Also keep in mind that it was African-American guitarists who mentored the Carter Family (Lesley Riddle), Hank Williams (Rufus Payne) and Johnny Cash (Gus Cannon), among others – the cases are legion. In the form of exchange, theft or parody, American music has evaded segregation. But the recording industry, motivated, in particular, by marketing considerations (racist intentions cannot be ruled out), has put genres into boxes and excluded black artists from the story they helped write, redirecting them towards rhythm’n’blues and its offshoots. In an interview with The Bitter Southerner, Ken Burns notes that country itself has fallen victim to this trap, to the point of being mocked for the clichés it conveys: “We make fun of it. You know, it’s about good old boys in pickup trucks and hound dogs and six packs of beer, when, in fact, it is actually dealing in a very simple but very direct way with universal human experiences”.

In his book on the matter, Country Soul – Making Music and Making Race in the American South (2015), Charles L. Hughes details the relationships between black and white musicians in the studios of Memphis, Nashville and Muscle Shoals from the 1960s. Besides the pioneer DeFord Bailey, Louis Armstrong collaborated with the country star Jimmie Rodgers on “Blue Yodel Number 9” as early as 1929, before many African-American musicians tackled the genre successfully, from Charley Pride to Ray Charles (notably on his album Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music in 1962).

In the 2000s, it was the turn of Darius Rucker, while Beyoncé sang “Daddy’s Lessons” (from her album Lemonade) with the Dixie Chicks on stage at the 2016 Country Music Association Awards. The performance may have earned her racist insults on social media, but it also helped open the door through which Jimmie Allen and Kane Brown rushed, bagging top spots in the Billboard single (“Best Shot”) and album (Experiment) charts in 2018. While both have also denounced the obstacles put up against them because of the colour of their skin and condescending remarks about their success, the lines clearly seem to be shifting.

Country music is getting its groove back, at odds with reinvigorated white supremacism, heckled by a black rapper with a pink hat.